The closing date remains fluid, but at some point in 2021, Koelbel & Company will sell the last of the 556 properties it developed in The Preserve at Greenwood Village—the exclusive enclave highlighted by lush open space (including the 55-acre Marjorie Perry Wildlife Preserve) north of Orchard Road between South Holly Street and Colorado Boulevard.

This milestone transaction will come 50 years after Walter A. Koelbel, the company’s late founder, purchased the first 280 acres of what would become the 522-acre Preserve, and 32 years after his son, Buz Koelbel, who ascended to the helm in 1985, finally broke ground on it.

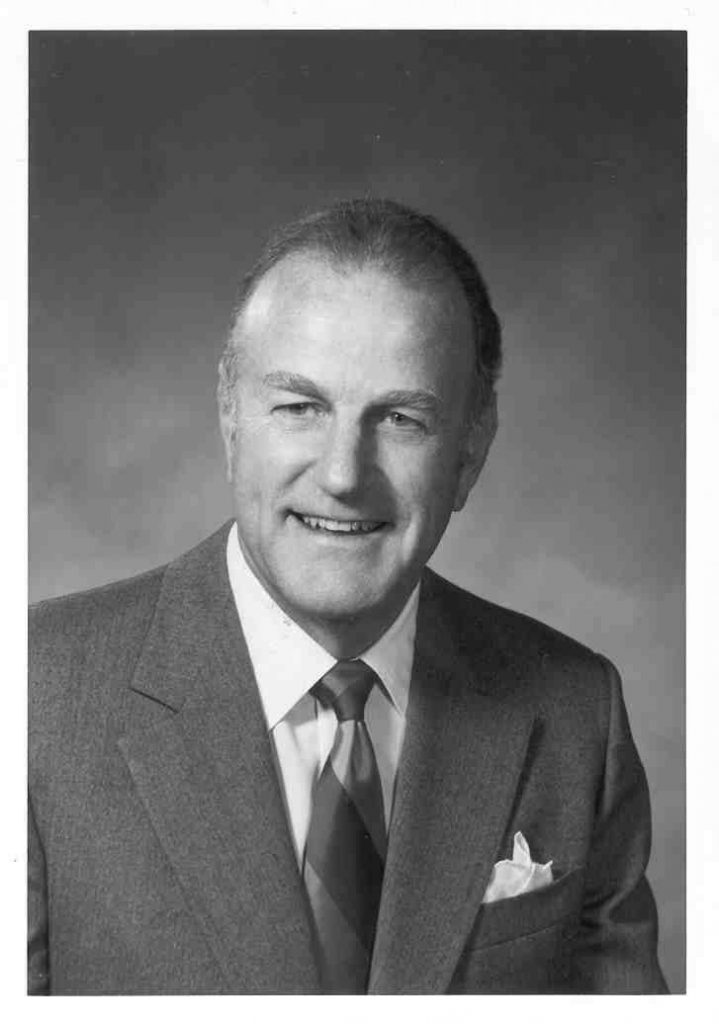

Walter A. Koelbel

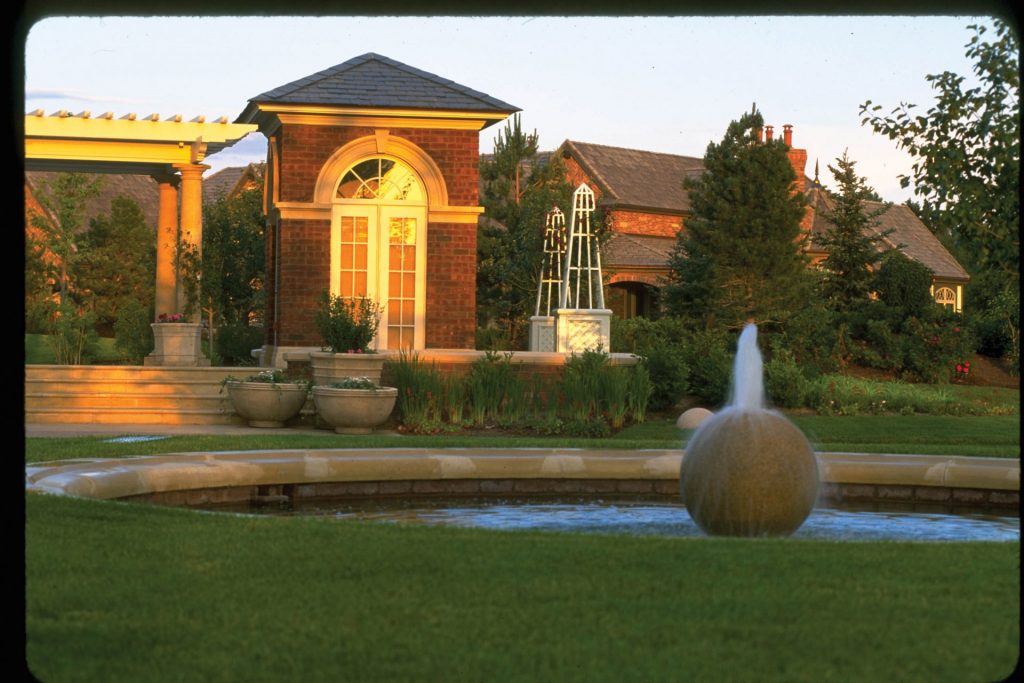

The Preserve

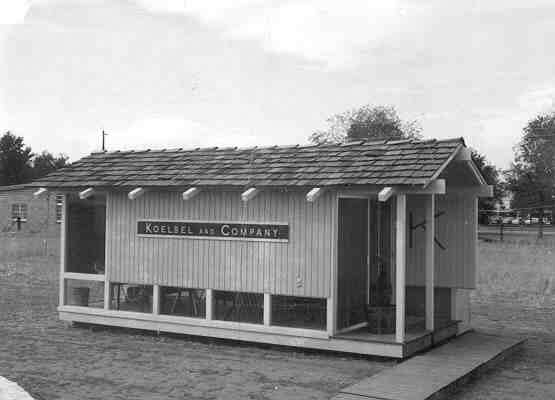

Koelbel’s First Sales Office

Koelbel’s First Sales Office

Cherry Hills Village

“Patience is genius,” Buz says, repeating one of his father’s guiding principles. “If you can position yourself to be patient, you can respond to the market.”

Koelbel dispenses this nugget while seated at the head of a conference table in the building his company owns at I-25 and Yale Avenue. It will be the first of many axioms prefaced by some variant of “as my father would say…” during a two-hour conversation. Flanked by his three thirtysomething sons—Carl, Walt and Dean, each of whom has joined the firm—the affable 68-year-old president and CEO doubles as both the successful scion and proud paterfamilias of a thriving family business now in its third generation.

All three of those generations have called Cherry Hills Village home, and they have conscientiously transformed much of it and the surrounding areas into the highly desirable South Suburban communities in which we live, work and play.

The Koelbel Buzz

The Koelbels have shaped the South Suburbs for as long as Walt Koelbel Jr.—the second child of Walter and Gene Koelbel—has been called Buz. Which amounts to the few days between his birth and when his toddler sister Lynn endearingly kept mispronouncing “baby brother” as “baby buzzer.”

That was 1952, the same year Buz’s 26-year-old father, a Michigan native armed with a University of Colorado business degree, left a real-

estate broker’s job to open what would become one of Colorado’s largest real-estate development, management and investment operations.

“Early on, my dad realized that dealing with the real-estate agents and the brokers wasn’t as much fun as looking for good land and figuring out what to do with it,” Buz explains. “His motto was, ‘Never forget, under all lies the land … we must protect it and use it wisely.’”

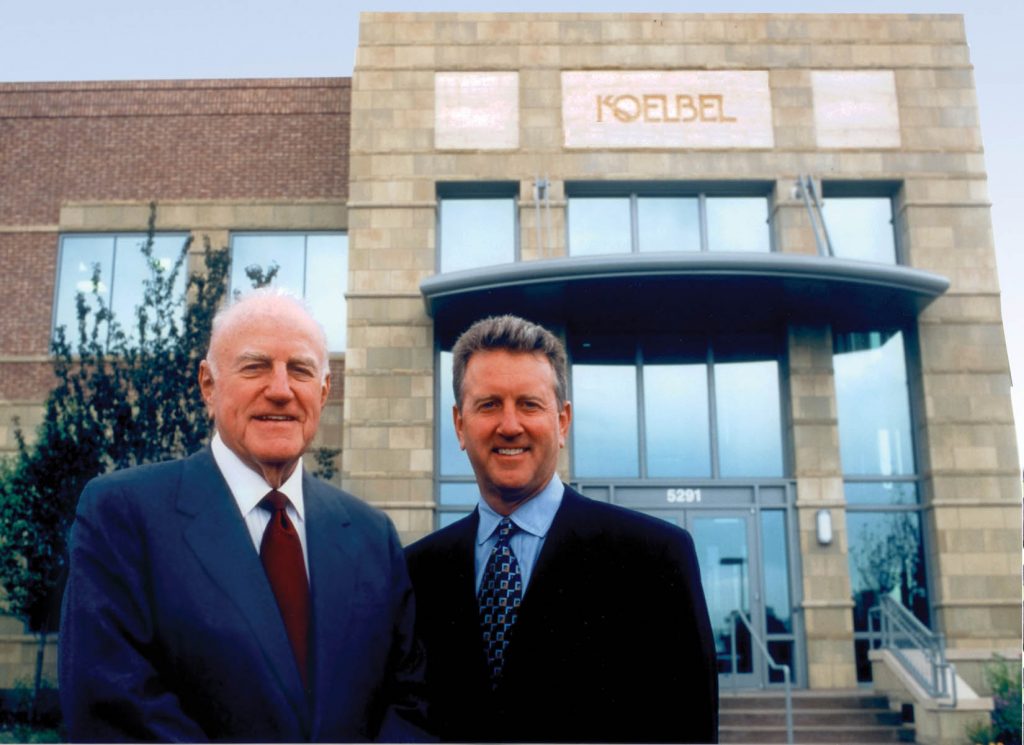

Walter and Buz Koelbel

Cherry Hills Village had only incorporated in 1945, and much of that “good land” was owned by farmers and the heirs of pioneers along the southern edge of Denver, near the Valley Highway that would become part of I-25.

Fueled by the potential of the location, Walt Koelbel pursued parcels along the emerging growth corridor. By the early 1960s, he’d built five neighborhoods—Charlou, Cherry Ridge, Cherryvale, Martin Lane and Mansfield Heights—that helped define the prestige of

Cherry Hills Village.

“Back then everything about real estate was parochial,” Buz explains. “There were no national shopping center developers, no national realtors, no apartment companies. You kind of picked the space you were in and did it geographically.”

Even when Walt Koelbel didn’t pick the space, he exhibited a foresight that would become his trademark. In 1956, when his father-in-law, the industrialist Carl Norgren, challenged him to develop the 600-acre cattle ranch Norgren owned on what was, at the time, literally on the wrong side of the tracks along Santa Fe, young Walt transformed Norgren’s Pinehurst Farm into the trendsetting Pinehurst Country Club, Colorado’s first master-planned community to use a golf course specifically to create aesthetic value for residential sales.

After graduating from CU and spending a couple of years in San Francisco, in 1976 Buz joined his dad in the family business. “It was kind of in the DNA,” he says. “He had me running at his hip, learning as much as I could as fast as I could.”

Buz tried to replicate the Pinehurst golf-course community model on the land his father had purchased in Greenwood Village. Five more acquisitions—the largest being “The Preserve,” a 210-acre estate of the late mining heiress and animal lover Marjorie Perry—nearly doubled the acreage to 540.

Buz engaged Jack Nicklaus to design the course, but the Greenwood Village city council nixed the plan. Buz persevered, changed the proposal and strategy, and instead of becoming Greenwood Country Club, in 1989 the land became The Preserve at Greenwood Village, eventually winning the Denver Homebuilder’s Association’s BAR Award for “Best Custom Community.”

The following decade, Buz further burnished Cherry Hills Village’s reputation by developing Cherry Hills Park, a tony 80-acre community of two-acre lots directly across University Boulevard from Cherry Hills Country Club.

By then, he had taken over daily operations from his father and the company had expanded into other parts of the Metro area, creating, among other notable projects, the 1,523-unit Breakers Resort apartment complex on Windsor Lake in southeast Denver and purchasing or developing commercial spaces such as Louisville’s Centennial Business Park.

The turn of the millennium brought the purchase of land for legacy residential developments: a magnificent 1,100-acre portion of Douglas County’s legendary Cherokee Ranch now known as The Keep; and Rendezvous Colorado, a four-season, activity-rich, master-planned mountain community just minutes from Winter Park in Grand County.

Rendezvous carries special significance for Buz, whose grandparents, Carl and Juliet Norgren, owned the nearby 446-acre Byers Peak Ranch. Although the property earned notoriety as President Dwight Eisenhower’s “Western White House” (a bronze of the Norgrens’ frequent visitor fishing the Fraser commands a corner of the Koelbel conference room), Buz fondly recalls visiting with his parents and siblings, learning to cast on Lake Mary and to ski at Idlewild. “It was a great gathering place,” he says of the ranch.

Pinehurst Golf Course

Pinehurst

The Preserve

Rendezvous

Creating Community

The concept of gathering is central to Koelbel ethos. “We’re about creating reasons for people to gather and connect,” Buz says. “It’s not just about building houses; it’s about building community and connections.”

On the residential front, this manifests itself in providing the “best of town and country,” with access to retail and restaurants, health services, public transportation, community centers and cultural venues as well as abundant open spaces, nature trails and recreational amenities. “Cherry Hills and Greenwood Village epitomize this,” he says.

“We tend to look at how impactful we can be to each individual family,” Carl Koelbel, the company’s chief operating officer and oldest of Buz’s three sons, explains. “We’ve never counted how many lots we’ve sold or platted.”

Credit for this approach, Buz elaborates, comes from using the same land planner, Jeff Vogel of Denver-based Vogel and Associates, for more than three decades. “He knows philosophically that we don’t start a plan saying, ‘How much density can we get?’ We start out saying, ‘How do we best utilize the property?’”

Over the course of the last decade, the Koelbels have succeeded at bringing the residential community approach to the commercial space. In 2014 the company opened Industry, a four-acre, single-story workplace on Brighton Blvd. and 30th Street, bringing Denver its first true industry-agnostic co-working space, with 65 businesses officing on one floor plane and using the same common areas and restrooms.

Four years later and five blocks north, Koelbel springboarded that philosophy into Catalyst, an “innovation ecosystem” focused on one industry: healthcare. The seven-story building houses more than 50 cross-pollinating tenants—ranging from Kaiser Permanente to SeaStar Medical.

Industry

Yale Station

Rendezvous

Rendering of the Ridgegate Project

Speaking of Healthcare …

How has the pandemic affected the overall Koelbel business and how will it affect it?

On the residential side, the “unprecedented times” of 2020 produced an equally unprecedented 113 property sales for Koelbel.

On the commercial front, “the pandemic highlighted and accelerated somewhat the underlying trends that were going on,” Carl explains. “One of those is remote work, with which we’ve just had a massive nationwide forced experiment. Folks are finding out that it probably works for more people than expected. You also have the fact that retail is really struggling, because we are so over-retailed compared to other countries. Our retail square foot per capita is something like 25 in the US and like four

in Germany.”

Pair these two trends—people dispersing how they work and live with fading malls boasting high visibility but low tenancy—and you get “some interesting opportunities” for repurposed space.

“We’re going to come out of this with the flexibility of employers allowing their employees to work in other places, but there will still be physical assets of an office for people to collaborate,” Carl predicts. “On Zoom, when the meeting starts, it starts; and when the meeting ends, it ends. The best interactions come after meetings. You need to have a place where you can be together. It’s the same with communities. Running into someone in the hallways of a country club, or in a community room at an apartment building … when people lack those interactions, it starts to take a toll.”

KUVO Studio

Walt, Carl, Buz and Dean

Giving Back

“We develop community in the community, so we need to give back to the community,” Buz says, quoting his father. Buz has walked that talk, directing much of his largesse towards education—“the most important thing for the future of our state and our communities.”

That commitment finds expression in 75 years of family involvement in the Sewall Child Development Center, the Fillmore Street headquarters of which is called the Koelbel Building in honor of Buz’s parents, Walt and Gene. Buz also paid the center full market value for its previous headquarters and actively raises funds for programs to help serve financially, physically or mentally challenged children between the ages of one and five years.

At the University of Colorado’s Leeds School of Business in Boulder, all classes now take place in the Koelbel Building—the result of a lead gift from Buz, who, along with both parents and son Carl, received degrees there. The Koelbel Library has stood across from The Preserve at the corner of southwest corner of Holly and Orchard since 1992.

And for 30 years, Buz and his wife Sherri have sat on the board of Economic Literacy Colorado, formerly the Colorado Council of Economic Education. “Our simple goal is teaching the importance of free-market capitalism, our freedoms, property rights and rule of law to K through 12 students so they understand the foundational principles of the country,” he explains.

“There’s also a cultural aspect to our communities we don’t ignore,” Carl points out. Sherri recently chaired the Denver Zoo board of governors, and a family contribution to Rocky Mountain Public Media gave Koelbel naming rights to the KUVO studio. Buz also notes that he’s arranged for RMPBS to air a show about the Colorado Business Hall of Fame, whose laureates include Carl Norgren and Walt Koelbel.

To serve all members of the community, the Koelbels are starting construction on their 10th and 11th affordable-housing projects since 2010—one of which, the first-ever in Lone Tree, is the located at Ridgegate stop on the light rail. “There used to be a stigma,” says Carl, who has spearheaded the initiative. “When people think ‘affordable housing,’ they think Cabrini Green in Chicago. It’s not like that anymore.”

Watching The Sons’ Rise

Buz grew up in Cherry Hills Village. It’s where he and Sherri raised their four children (their youngest, Bethany, works at a Denver-based computer firm), and where Carl, Walt and Dean all live with their respective wives and three children less than a mile from their childhood home on East Oxford Avenue near Dahlia Hollow Park.

“We all chose a 1970s ranch that needed a lot of work rather than take the same amount of money and getting twice the square footage down in Highlands Ranch,” Carl says. The appeal, he says, comes from living in a community where “your kids can have the same kinds of memories that you had as a child—of going to the Highline Canal or Cherry Hills Elementary School—and where you could still play golf with some of the people you’ve known since first grade or as junior golfers at Cherry Hills.”

In addition to having plenty of room for those nine grandkids all under the age of six, Buz and Sherri’s current home—a scrape of a house once belonging to a U.S. president’s brother-in-law—brims with Colorado pride: a commissioned painting of Byers Peak and Lake Mary by Parker artist Jay Moore; a shimmering display of rhodochrosite, topaz and other Colorado-mined gemstones and minerals; and a pair of snow-white ptarmigans sculpted from Sivec marble by Loveland’s Ellen Woodbury.

Buz enjoys having his sons close and getting to work alongside them—something he insists was never discussed when they were young.

“Well, there was a discussion,” Carl clarifies with a laugh. “And the discussion was…don’t. He literally took each of us to San Francisco when we were in eighth grade, and the message was twofold: one, to empower us not to feel obligated; and two, that this industry is extremely difficult and why would you be dumb enough to get into it?”

“We couldn’t get away from it, so we each found our own way back to it,” Dean says. “It wasn’t something we felt we had to do, nor that we were necessarily encouraged to do, but what we wanted to do.”

Their parents did insist they all leave the state for college. “I think if there wasn’t such a sense of community in Cherry Hills that they wouldn’t have been so inclined to send us away,” Dean says. After graduating from Cherry Creek High School, Carl went to USC, Walt to the University of Kansas and Dean to the University of Indiana. Post-college, the three continued to pursue lives away from Colorado. “But when you come back, that’s when you realize how great this place is,” Walt admits.

Carl returned first, earning his MBA at Leeds in 2010 and becoming Koelbel & Co.’s chief operating officer. Dean joined him years five later as the director of leasing operation and business development. The following year brought Walt into the fold as the director of commercial real estate.

“We all followed different routes back to real estate.” Carl observes. “We all ended up here, but we didn’t come through the same door. There’s enough to do, so there are no turf wars.”

Bearing the Koelbel surname comes with enormous responsibility—especially as members of the third generation, a threshold only one in every eight family-owned concerns are fortunate to survive. The good news is that with the sons now in the fold, Koelbel has continued to pursue the pioneering, ahead-of-the-trend path that has always defined its success. The company has even begun to look at out-of-state development for the first time.

“We’ve had the opportunity to do amazing things being part of the family and part of the company,” Carl says. “But at the same time we’ve had to be very careful about how we do that, and do it responsibly.”

“It goes back to some of the lessons Dad and Papa taught us,” Walt adds. “It’s important to have good goals, but you can’t cut corners; you can’t do it the wrong way. We’re all around here, we’re in the community. If we do something the wrong way and people start not to trust us, then we’re not going to be able to do what we do. The third generation doesn’t want to screw up the 68 years’ worth of goodwill and trust in the name, in the company and in the family. Keeping our eye on the small things helps not hurt anything on the bigger side.”

Buz listens, secure in the knowledge the business his father started in 1952 will endure. “The pleasure and reward to do what I’m doing with the three of them,” he says with great pride, “exceeds anything I thought it might be.”