By Lexi Marsha

THE VERTICAL FACES of Colorado’s peaks have always drawn dreamers and pioneers—those who see not just rock and ice, but possibility. From the early 20th century to the present day, certain individuals have left indelible marks on the state’s outdoor culture, transforming how we climb, conserve, and celebrate wild places.

THE PROFESSOR WHO OPENED THE PEAKS

Long before modern climbing gear made ascents routine, Albert R. Ellingwood was already rewriting what seemed possible in Colorado’s high country. Born in 1887, Ellingwood combined the precision of an academic—he was a Rhodes Scholar and political science professor at Colorado College—with the audacity of an explorer. His legacy rests on a remarkable string of first ascents that opened some of Colorado’s most formidable terrain.

One of Ellingwood’s most celebrated achievements came in 1916 when he and pioneering female alpinist Eleanor Davis made the first recorded ascent of Crestone Needle in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, often cited as the last of Colorado’s fourteeners to be climbed. His 1920 first ascent of the intimidating Lizard Head in the San Juan Mountains with Barton Hoag further demonstrated his calculated boldness. As Ellingwood wrote in Outing Magazine in 1921, “The government geologist had said the Lizard Head was inaccessible, and the Forest Service pamphlet corroborated him: ‘The sheer rock face of Lizard Head Peak (13,156 feet) has never yet been climbed by man.’” The technical difficulty of the climb, attempted at high altitude with equipment that would seem primitive by today’s standards—hemp ropes, hobnailed boots, soft iron pitons, and unwavering nerve—demonstrated his exceptional skill.

What made Ellingwood revolutionary wasn’t just his climbing ability, but his methodology. He brought scientific rigor to route-finding, carefully studying approaches and conditions before attempting climbs. He climbed with accomplished partners, helping establish that these peaks belonged to anyone with the skill and determination to climb them. In the same Outing article, Ellingwood also wrote, “‘Inaccessible’ and ‘unclimbable’ are strong words and are like a red rag to the enthusiastic alpinist.”

Ellingwood’s influence extended beyond his own ascents. He mentored a generation of Colorado climbers and helped establish mountaineering as both sport and science. When he died in 1934, he left behind a transformed landscape where dozens of once-impossible peaks now had routes to their summits.

THE PHOTOGRAPHER WHO CHANGED MINDS

When John Fielder lifted his large-format camera toward Colorado’s wildest places, he wasn’t simply admiring scenery—he was building one of the most persuasive conservation cases the state had ever seen. His philosophy was straightforward: If people could see Colorado’s imperiled landscapes with clarity and awe, they would fight to protect them. As Katherine Mercier, exhibition developer and historian at History Colorado, puts it, “His goal was to use his photos to make the world a better place.” And for decades, he did exactly that.

Fielder’s influence stretched far beyond his more than 40 books and coffee-table volumes. His photographs became traveling ambassadors, reaching residents who would never summit a fourteener or trek into the Weminuche Wilderness. In suburban living rooms and legislative committee rooms alike, his images transformed abstract land-use debates into visceral encounters with real, living places. Experts say that emotional connection helped shape policy. In 1992, Fielder spent a year crisscrossing Colorado to campaign for Great Outdoors Colorado, using his slide shows and public talks to articulate what was at stake. That next year, his advocacy—book proceeds, statewide talks, and endless miles of driving—helped build the groundswell behind the Colorado Wilderness Act. “He was a fabulous advocate for our wild places,” Mercier says. “These efforts mattered.”

Behind each iconic image lay an almost obsessive commitment to preparation. Fielder mapped routes with pinpoint GPS precision, sometimes planning for months just to capture the exact angle of a purple alpenglow one particular evening each year. He traveled with sherpas, hauling gear across remote terrain and surviving on ramen to reach the perfect vantage point. These behind-the-scenes details, part of Fielder’s extensive archive now held by History Colorado, reveal a man whose devotion to place was as rugged as the landscapes he documented.

His impact continues to evolve long after his passing in 2023. In donating more than 6,000 photographs, maps, and field materials to History Colorado, Fielder made a clear statement about legacy: His images should continue inspiring future generations to become stewards of the land. “He wanted people to understand that these are real, breathing places—and that they depend on us,” Mercier says. History Colorado’s exhibition, “Mountain Majesties: On the Summit with John Fielder,” brings that message into sharp focus. Uniquely curated in collaboration with museum members, the show displays photographs chosen for the emotional resonance they evoke—wildflower fields, winter ridgelines, luminous lakes—each paired with personal reflections on why the image, and the place, matters. The result is less a traditional gallery than a kind of communal hike through Colorado’s seasons alongside Fielder himself. For Mercier, that sense of shared wonder is central to his legacy. “I wanted pieces that capture that moment of awe—you look up at the Front Range on the way to the grocery store and think, ‘Wow, this is Colorado,’” she says. Fielder understood that awe is not incidental. It is catalytic. It is how minds change, how constituencies form, how landscapes endure.

THE RANCHER WHO SAVED THE LAND

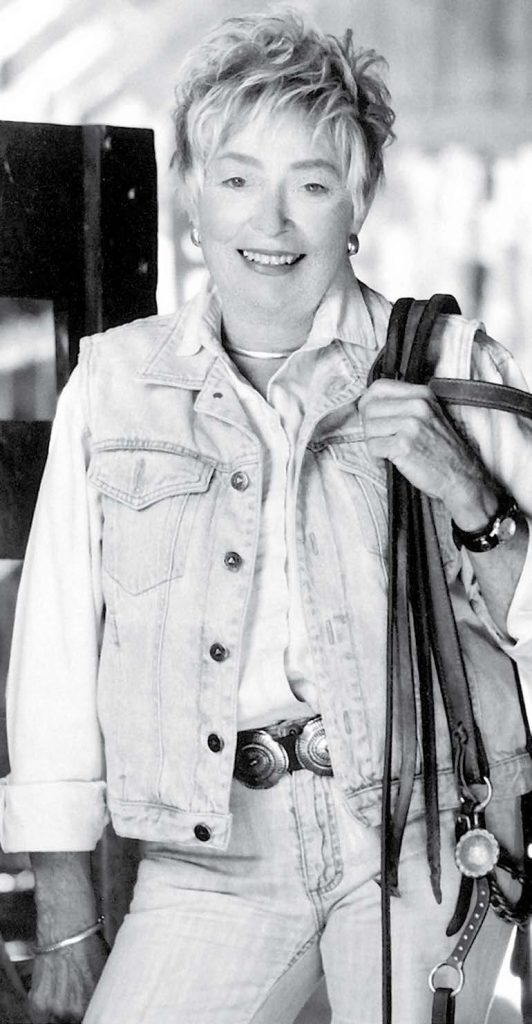

Sue Anschutz-Rodgers understood something crucial about the American West: One of the greatest threats to its wild character wasn’t necessarily public development, but private subdivision. A rancher and member of one of Colorado’s prominent families, she recognized that keeping working landscapes intact was essential to preserving the region’s ecological and cultural fabric. Her efforts helped advance conservation easements—an approach that has since protected hundreds of thousands of acres across the West.

The concept was elegant in its practicality. Rather than buying land outright—often financially impossible for conservation organizations—easements allowed landowners to voluntarily restrict development rights while retaining ownership. Ranchers could continue working their land, passing it to their children, but the property could never be subdivided into ranchettes or shopping centers. For many families deeply attached to their land but facing crushing estate taxes or economic pressure to sell, easements offered a lifeline.

The owner of Crystal River Ranch in the Roaring Fork Valley, Anschutz-Rodgers demonstrated its viability as a working rancher. She was instrumental in establishing the Colorado Cattlemen’s Land Trust, a land trust focused on agricultural lands, and has served on its board since its founding. The ripple effects of this work are visible across Colorado today. Open ranchlands that provide wildlife habitat, preserve scenic vistas, and maintain connections between protected areas increasingly carry conservation easements. The approach has allowed organizations to leverage limited budgets into vast protected landscapes. Among many philanthropic awards and honors, Anschutz-Rodgers’ environmental contributions led to her induction into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame in 2008. Now approaching 90 years old, her legacy lives on in the landscapes she helped protect.

THE GEAR REVOLUTIONARY

Ray Jardine was born in Colorado Springs, where Pikes Peak and nearby crags provided his climbing education. But he would ultimately revolutionize climbing worldwide through a simple yet radical innovation: spring-loaded camming devices. In the 1970s, Jardine introduced “Friends”—devices that could be quickly placed and removed from rock cracks, leaving no trace. Before this invention, climbers relied on hammering pitons into cracks—a destructive, time-consuming process that scarred rock faces.

The impact was seismic. Suddenly, routes that had required hours of hammering could be climbed quickly and cleanly. The clean climbing movement, which emphasized leaving rock unaltered, gained practical tools that matched its ethical aspirations. Jardine himself pushed standards with audacious climbs that showcased the new technology, including making the first free ascent of The Phoenix in Yosemite in 1977, which was then the world’s hardest trad climb.

But Jardine’s contributions extended beyond climbing. He became equally influential in backpacking, championing ultralight techniques decades before they became mainstream. His philosophy was to strip away everything unnecessary, move faster and farther, and reconnect with the essential experience of wilderness. Alongside his wife Jenny, the Jardines challenged the conventional wisdom that comfort required pounds of gear, instead proving that skilled lightweight travelers could cover more ground while treading more lightly on the land. His books, including The PCT Hiker’s Handbook, inspired thousands to reconsider their approach to backcountry travel. Now 81 years old, Jardine’s innovations continue to influence how climbers and backpackers approach wild places.

Among Colorado’s great mavericks—innovators, explorers, conservationists—these legends stand apart. Their medium: beauty, method: devotion, mission: protection. Their stories reveal how innovation, vision, and determination can reshape not just mountains, but movements.