How a Littleton man sparked Colorado’s “soccer explosion”

By Flint Whitlock

Photos courtesy Joe Guennel collection

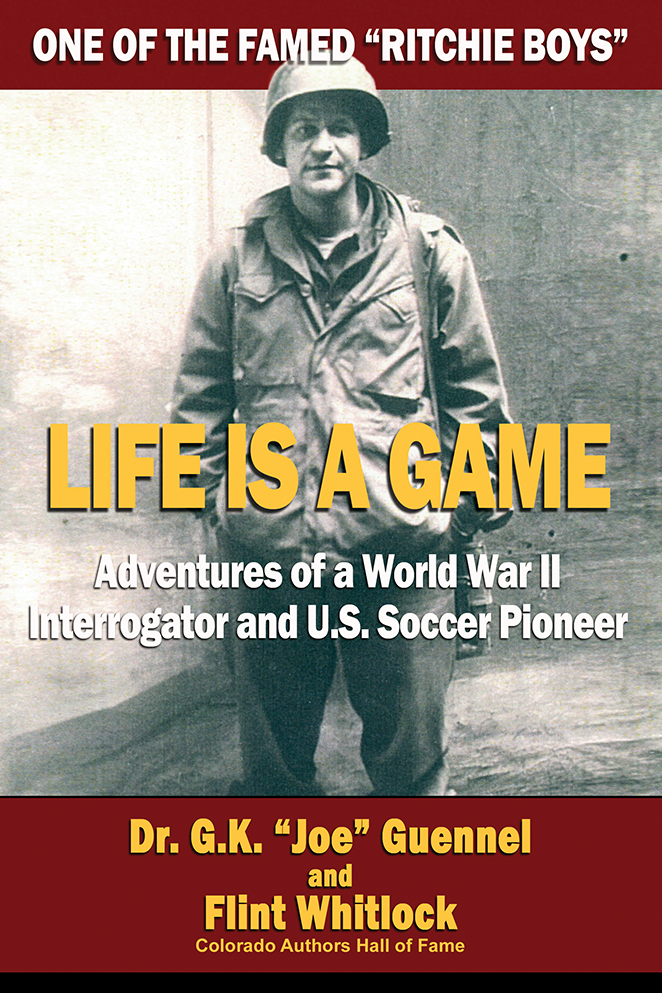

Flint Whitlock is a local military historian specializing in World War II. This content is based on his collaboration with Joe Guennel to edit the latter’s autobiography, Life Is A Game (Cable Publishing, 2021).

Looking around local parks and playing fields these days, filled with a colorful profusion of boys and girls kicking soccer balls while being cheered on by soccer moms and dads, it’s easy to think that the game has always been part of the American sporting landscape. But you’d be wrong to think that.

Sixty years ago, Littleton became the epicenter of a seismic shift of sport in Colorado—thanks primarily to the efforts of one man: the late Gottfried K. Guennel, an émigré from Nazi Germany. “Soccer didn’t simply spring full-grown like Athena from the head of Zeus,” Guennel said. “A lot of people and a lot of hard work went into making it happen.”

“Joe,” as Americans later called him, literally got the ball rolling. He and his parents escaped from Germany in 1934, just as Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party were coming to power. Like most European boys, his first love was soccer, and he became one of the best young players in Oelsnitz, near the Czech border.

But when he couldn’t find a soccer team to play with in his new town of Bangor, Pennsylvania, he turned to the uniquely American sport of baseball and discovered that his youthful athletic talents also extended to this activity.

With the world marching toward war in the late 1930s, Joe enrolled at Butler University to study forestry. After Pearl Harbor, he, along with millions of other young American males, enlisted in the U.S. Army. With his excellent grades, he was selected for the Army’s ASTP—the Army Specialized Training Program—established at hundreds of colleges nationwide; he was assigned to attend the University of Missouri.

The ASTP was a hothouse for breeding officers with special abilities; Joe happened to be fluent in German. Joe also organized a soccer team of fellow ASTPers, most of whom had never seen a soccer ball, simply to get a little exercise. Word soon leaked out about this ad hoc team, and a match was arranged between Joe’s team and the top high school team in the St. Louis area, one of the few soccer hotbeds in America at the time.

As the date for the game drew nearer, Joe became terrified that his soldiers would be badly embarrassed by the high schoolers, and he wanted to cancel the match; his players convinced him otherwise, and the team played in front of 4,000 spectators, ending in a 1-1 draw. Greatly relieved that it had not been a disaster, St. Louis sportswriters singled out Joe as the star of the Army team; praise would propel him to devote his life to soccer after the war.

The ASTP was canceled in April 1944 because of severe manpower shortages in the combat units, and Joe thought he would end up as a rifleman in a foxhole somewhere on the front lines. Instead, the Army sent him to Camp Ritchie, Maryland, where he took accelerated courses in how to interrogate prisoners of war.

After a few months of study, he was shipped to France, arriving there in November 1944. He was immediately assigned to Interrogation Team 124 and attached to the 3rd Infantry Division. The six-man team’s duty was to question German soldiers captured on the battlefield and obtain as much information from them about their units’ activities as possible.

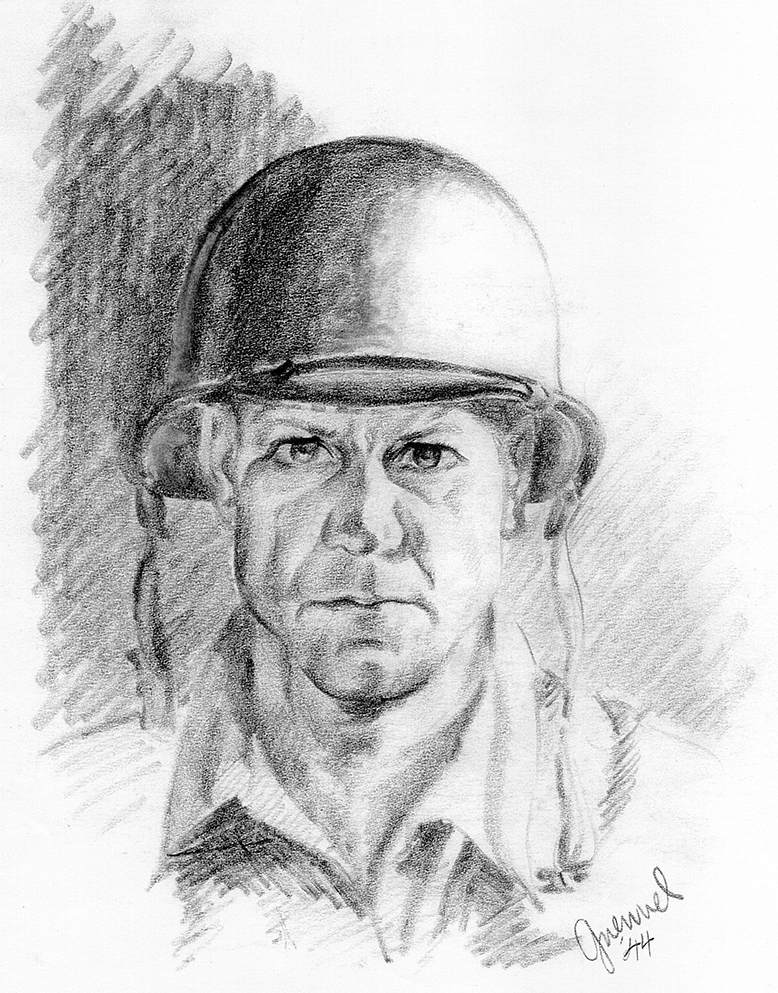

During much of his time overseas, Joe, an excellent artist, sketched and painted his way across Europe. As his unit neared Munich, they came across the newly liberated Dachau concentration camp, where piles of corpses presented a scene of unimaginable horror.“Those images are burned indelibly in my brain,” he admitted. Stunned, Joe threw some of his packaged rations over the barbed wire, where thousands of starving inmates hungrily grabbed them. To recover from the nightmare, Joe and his team took a jeep trip south to Berchtesgaden, home of Hitler’s alpine retreat on the Germany-Austria border and the Third Reich’s purported “final redoubt,” where the Allies expected the Nazis to make their last stand.

The clean mountain air and glorious vistas were a refreshing tonic from the awfulness of Dachau. Believing that his team was the first group of Americans to reach the area, Joe and his buddies rampaged through Hitler’s bomb-damaged “Berghof” and carried off souvenirs; Joe took an ashtray, a small plaque and a bath towel. Before returning to their unit, the team also nabbed a sled full of wine from secret passages below the SS canteen.

Once the war ended, Joe was selected to interrogate some of the top Nazi generals and administrators. He thought he would be assigned to be an interpreter at the Nuremberg War Crimes Tribunal in 1945, but that assignment didn’t come through. He stayed in war-torn Germany for a couple of years, even marrying a German girl named Hilde Lang.

The two of them then came to the U.S., where Joe enrolled in a graduate program at Indiana University and earned his doctorate in palynology. While there, he organized and coached the school’s first club soccer team in 1949. (After becoming a varsity team in 1973, Indiana eventually became one of the most successful, winning eight NCAA and 18 Big Ten titles.) With his degree in hand, Joe began applying for jobs, finally landing one with Marathon Oil in Littleton in 1961.

Soccer soon became his focus again. He met with the athletic director at the University of Denver and helped the school start a soccer program to replace its now-defunct football team. He was becoming nationally known when he became the secretary-treasurer of the fledgling National Soccer Coaches Association of America.

Seeing no one playing the sport in Littleton’s parks and schools, Joe, like an artist viewing a blank canvas as having unlimited potential, met with a local man, John Meyer, who had just organized a couple of kids’ teams. But Meyer soon moved away, leaving the field open to Joe. “I wanted to do what I could to promote kids’ soccer in Colorado. Nobody asked me to do it, nobody said I would get rich or famous doing it, but I did it anyway,” he said. “I wanted American kids to have an alternative to the other American sports such as basketball and football—especially kids who weren’t big enough for football or tall enough for basketball. Soccer was perfect for the ‘average’ kid.”

It didn’t take long before Littleton’s parks were alive with children kicking balls around. And Joe was the driving force behind it. “I built the portable goals, lined the fields, wrote news releases and bought soccer balls from a mail-order supply house in New York,” he said, “because the local stores didn’t sell them. And my wife washed the uniforms.”

Joe also taught coaches how to coach and referees how to referee. He fund-raised, coached, refereed, held player and coach clinics, and did whatever else was necessary to get this new and alien sport off the ground. But there was a sticking point: the schools. “I tried to get the schools to add soccer to their athletic programs but got a lot of resistance from athletic directors—especially football coaches who saw soccer as a threat. It would take a while before the high schools finally added soccer.”

The first Denver-area high school league adopted the sport in 1968, and the Colorado High School Activities Association (CHSAA) sanctioned the sport in 1971.

As the years went on, the sport continued to grow in Littleton and beyond as Joe applied his talents to helping other communities—in Texas, Ohio, Montana, and Oklahoma—start their own youth programs. He became the “Johnny Appleseed of American soccer.”

It also took a while for professional soccer to take root in Colorado. The first pro team—the Denver Dynamos of the North American Soccer League—began play in 1974 but moved to Minnesota after two years. The Dynamos were followed in 1978 by the Colorado Caribous and the indoor Denver Avalanche (1980–1982), but they, too, faded from the scene. It was not until 1995 when the Colorado Rapids, owned by Kroenke Sports, came into being as one of the original teams of Major League Soccer, built an 18,000-seat stadium in Commerce City and won the championship in 2010 (ex-Denver South High School star Conor Casey scored the winning goal).

In addition to the Rapids, two other professional teams have begun operations—the Colorado Springs Switchbacks of the United Soccer League and the Northern Colorado Hailstorm FC in Windsor (of the USL’s League One; one of the owners is former Colorado Rockies outfielder Ryan Spilborghs).

Since Joe Guennel’s pioneering work, soccer has continued to grow. The Colorado State Soccer Association reports that in 2023, more than 60,000 children played on 1,190 competitive and 600 recreational teams, while more than 1,600 adults played on 82 teams.

Colorado soccer made great strides and gained national recognition. Dr. Robert Contiguglia of Littleton served as president of the U.S. Soccer Federation from 1998 to 2006 and helped the U.S. host the 1999 Women’s World Cup. Coincidentally, the Colorado Rush Nike Girl’s Soccer Team, based in Littleton, was the first girls’ team in U.S. Youth Soccer history to win three consecutive national championships. Their Under-17 team won the cup in 1999, the U-18s won it in 2000, and the U-19s won it again in 2001.

Dozens of Colorado kids who first fell in love with the sport that Joe Guennel founded in 1961 have gone on to play professionally both in the U.S. and abroad. And the very best have established themselves on the U.S. Men’s and Women’s National Teams. April Heinrichs of Denver was captain of the U.S. Women’s Team that won the very first FIFA Women’s World Cup in 1991 and was the national team’s head coach from 2000 to 2005. More recently, players such as Mallory Pugh Swanson of Highlands Ranch (who played her amateur soccer with Littleton’s Real Colorado team), Lindsay Horan of Golden and Sophia Smith of Windsor have become the stars of the U.S. Women’s National Team.

For his lifetime of contributions to the sport, Joe Guennel in 1980 was inducted into the U.S. Soccer National Hall of Fame. Sadly, Joe passed away in 2013 and was laid to rest beside his first wife at the Fort Logan National Cemetery in Sheridan, Colorado. Yet his most significant achievement—establishing soccer in Colorado—will never die.