Photos courtesy Project C.U.R.E.

Nearly a quarter of a century ago, Douglas Jackson was embarking on his first needs assessment trip with Project C.U.R.E. to find out how the nonprofit could best serve hospitals and clinics in Bolivia. As the plane descended on La Paz, he looked out the window at the sprawling city. His dad, Jim, the founder of the Centennial-based humanitarian relief organization, nudged him and said: “Don’t lose your heart here.”

“What do you mean?” Jackson responded.

Then, his dad gave Jackson a bit of wisdom that’s stuck with him to this day: “Most people fall in love with the first place they work at with us, and then get locked into going back to that one place. We have the entire world to serve. You can’t afford to fall in love with only one part of it.”

Since its inception more than three decades ago, Project C.U.R.E. has brought medical supplies and equipment—items like beds, gloves, CAT scan units—to 138 countries, ultimately empowering doctors and nurses to save lives. The organization is bridging a gap: Thousands of people in the developing world die every day of treatable illnesses because local hospitals don’t have adequate medical supplies. The organization also helps train nurses, midwives and birth attendants. In Ghana, for instance, midwives learned lifesaving skills that allowed them, in one year, to save 184 babies born with primary apnea.

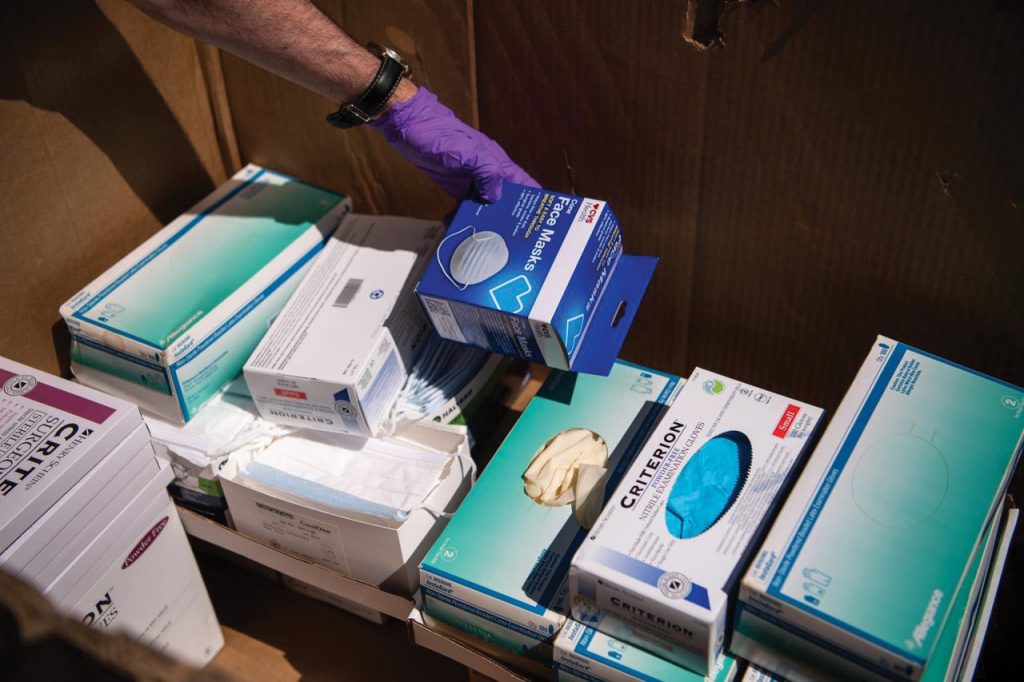

Since March, saving the world has started at home. Due to the spread of the novel coronavirus, the nonprofit has temporarily shifted its focus to the critical needs here in the United States, donating masks, sanitizer, protective equipment and other supplies to hospitals, emergency services and local governments in Denver, as well as Nashville, Houston, Chicago, Kansas City, Phoenix and around Philadelphia—all where Project C.U.R.E. has warehouse distribution centers. Jackson, who is president and CEO, tells us more about the work Project C.U.R.E.—which stands for Commission on Urgent Relief and Equipment—has done worldwide and how the organization is offering critical support right now.

How did Project C.U.R.E. get its start?

“My dad founded the organization with my mom in their Evergreen garage in 1987. He had been working as an economic consultant in developing countries. During a trip to Brazil, an interpreter—a medical student—took him to a clinic near Rio de Janeiro that was completely empty of supplies. He learned patients were often turned away because of the dire lack of medical provisions. He made a promise to the clinic doctor, and with the help of his friends in the medical industry, was able to gather $250,000 worth of medical supplies within a month to donate to the clinic.

“Now we have 32 paid employees, 35,000 volunteers and we have sent as many as 20 semitrailers filled with equipment into the developing world on a monthly basis. My dad is still on the board, and he and my mom live in that same Evergreen home.”

How has the organization been able to grow to have such a big impact?

“Our volunteers create the magic. We built an organization that’s truly focused on creating opportunities for them. My dad and I are not medical doctors. We’ve said to nurses: ‘This is your sandbox, tell us how this works. You’re in charge.’ Over the years, we’ve focused on prevention, diagnosis and treatment of diseases such as H.I.V./AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and Ebola.”

How has Project C.U.R.E been aiding in the COVID-19 response?

“We started getting requests from local health care providers—doctors, nurses, volunteers—who are on the frontlines and are running out of N95 masks, personal protective equipment and gloves. We’re in the United States, so you might think ‘wow, how can that be?’ It’s sobering, and it really speaks to how we need to get a handle on the supply chain here. Because of that demand, we’ve done something we’ve never done before and pivoted to donate 100 percent of the items that individuals and companies give to the local fight against COVID-19, to the brave men and women on the frontlines in our communities.

“We had an amazing outpouring of support at our first drive in Denver. One of the most poignant moments for me was when I was standing out there, directing traffic, and an older couple—who would be in the high-risk group—rolled down their window and handed over two canisters of sterile wipes. We had real estate agents donate shoe covers and construction firms donate non-sterile gloves. And the Metropolitan State University biology department donated lab masks. It was really touching.”

GET INVOLVED

Project C.U.R.E.

Centennial

303.792.0729