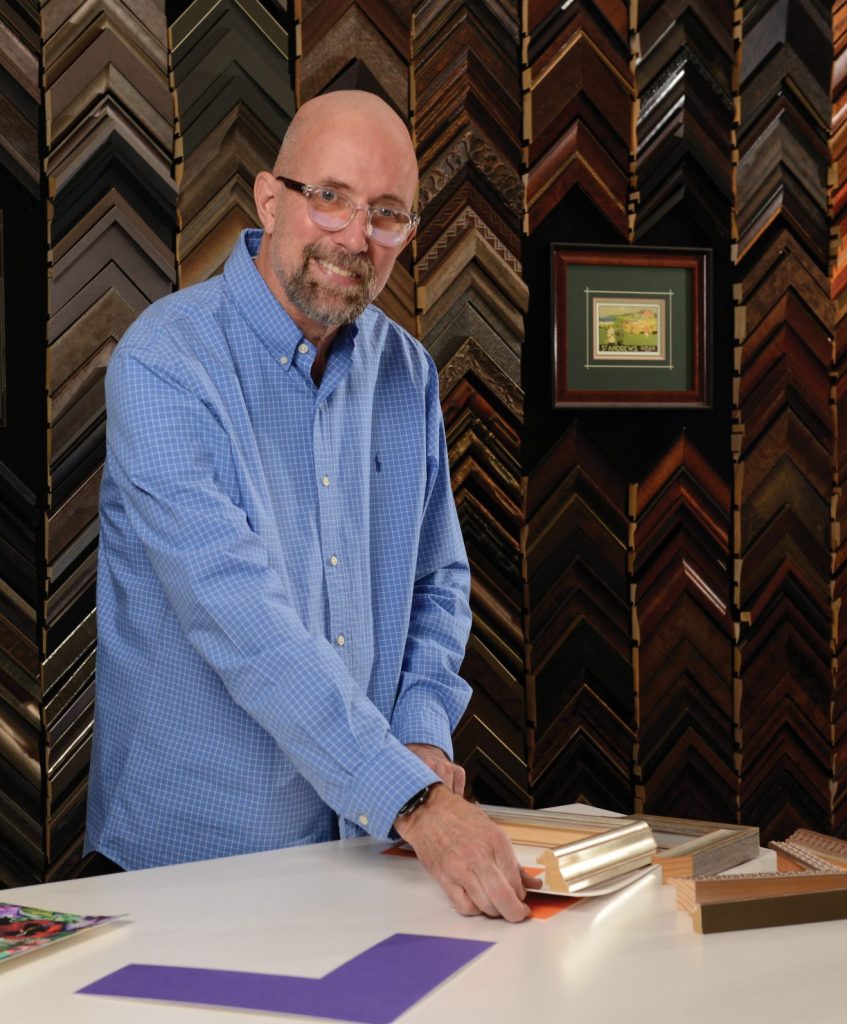

Photography by Chad Chisholm, Custom Creations

Anyone who doubts what a good frame can do doesn’t know the story of “Salvator Mundi.” Although it was valued at $100 million, the painting by Leonardo da Vinci became the most expensive piece of art ever sold in 2017—for a whopping $450.3 million at auction at Christie’s in New York. Some of its appeal: it was adorned with a rare 16th-century gold and black frame worth up to $50,000 itself.

This is just one famed example of how proper framing can exalt an already exquisite art piece. “It can make mediocre artwork look great and it can make great artwork look spectacular,” says Reed Masten, owner of Masten Fine Framing and Gifts. “We’ve all seen picture frames that look really bad.”

As if to counteract the world’s blight of bad framing, Masten’s shop is devoted to a myriad of superb options—with some 1,500 framing samples from all across the globe, ranging from water-gilded to metal and wood. But, more than an average frame shop, there’s something that’s led Masten to frame for everyone from the Denver Art Museum to a steadfast following of private collectors: His craftsmanship. “Frames are basically fine furniture!” Masten says. “When I first started my business, I made gold-leaf frames—I would make frames out of raw materials, then gesso them and put gold leaf on them myself.” Now, while Masten and his staff make nearly all of their frames on-site in their shop, their 12- and 22-karat gold options are made in New York by master craftsmen who hand-carve them with sgraffito, an Italian technique with cut corners and decorative notes, like shells.

“That’s the high-end side of framing,” when you have a piece of work that really warrants a fine case, Masten says. “They take so much time that I’d have to work at night to do them, and the New York people can do carving and other special techniques.” Outsourcing the task is well worth it—and faster than doing it in-house—for gilt frames, which can adorn a classic painting as beautifully as they can juxtapose modern art.

The options available at Masten Fine Framing and Gifts, and Masten’s museum-worthy handiwork, come backed by the power of decades of experience. He’s been making things by hand since as far back as age eight, when Masten recalls hawking handmade acorn pipes door-to-door. But he cashed in his retirement account in 1986 to start the shop after a former coworker at the Jefferson County Planning and Zoning department suggested it as a way to balance paying bills and making art. “Now at 63, I’m still talking about finding time to paint,” says Masten, who earned his Bachelor of Fine Arts at Syracuse University before moving to Colorado, entranced with mountain life. “But I surround myself with art—that’s pretty good.”

The shop relocated from Uptown Denver to Cherry Hills Marketplace two years ago, and is kicking off its 35th year in business. A portion of the store, which Masten says is a detail that sets him apart from the rest of the framing crowd, is devoted to gifts—greeting cards, pottery, clocks, easel-backed photo frames and more.

The typical framing job takes anywhere from two to four weeks; the hand-carved, hand-gilt options may take up to eight. You can stop by the Masten website to use a visualizer to “see” your piece framed before committing, but he warns that digital renderings are often off-color; it’s always best to come in and work with the Masten staff before making a choice.

The process is an art in itself, a bit like working with a professional interior decorator to design a room in your home: “We start out with a person’s style, asking them if they’re more contemporary or traditional. Are they eclectic? Do they like natural woods, or something more finished, like gold or silver?” he says. And don’t fret too much about other aspects of the room where the frame will be hung, like if the draperies will match. “We always frame to the art; we want the art to look good. And if the art looks good in the house then, theoretically, the frame will look good. It’s better to do something to enhance and protect the artwork than something that matches the room.” The best part of working with the pros at Masten: estimates are totally gratis. “We never pressure anybody to buy anything here; after this many years, it’s about making customers happy and finding what meets their needs.”

As of press time, the business is slightly backed up due to COVID-19-caused supply issues. “We had some really beautiful things happen during the lockdown though,” Masten recalls. “Our income basically stopped coming in, but we still had bills to pay. We had customers that brought in things to frame because they knew we needed work. And a couple customers sent us beautiful letters and even gifts and checks. An internet marketing sales rep we work with showed up one day and said, ‘I have four or five hours, if you have any kind of job you need me to do—whether it’s taking out trash or sweeping out the back room.’”

One bugaboo for any high-end professional framer these days: a dearth of quality wood. “Wood has become an issue on our planet and the wood we use in picture framing has to have no knots or imperfections, and has to stay flat and straight,” he says. “It’s getting harder and harder to source it for picture frames: Most of our old growth forests are either gone or not harvestable.” But Masten has found a sustainable solution: a line of green frames made from discarded wood products.

Over the years, Masten has framed all manner of things, from a 7-by-10-foot map so large it wouldn’t fit in the delivery van to a pair of ballet slippers from a client’s childhood, placed in a shadow box with the wallpaper from her then-bedroom. “The smallest thing we’ve ever framed was a Civil War uniform button. The glass for the frame was maybe a three- or four-inch square, but the frame itself was 12 inches wide, so it had this really large frame around a little teeny button.” In other words, it doesn’t need to be a da Vinci to warrant a gorgeous frame. As Masten says, “the frames themselves are art.”

MASTEN’S TOP FRAME STYLES

22-karat Gold Leaf: “My absolute favorite style! Potentially hand-carved, but definitely very traditional. You want to match the style of frame to the period of artwork; this would work wonderfully with a 1920s Art Nouveau piece.”

Shadow Box: “It’s fun because you get to show off little things that don’t fit in a flat frame in a way that makes them feel like an artifact. Let’s say you had an old land title document for a farm your grandfather bought back in the 1800s and you wanted to commemorate that. You could put it in a shadowbox still wrinkled and folded and torn, so it looks like a historic object.”

Ultra Contemporary: “Not metal, but something streamlined and modern. Very clean-lined and minimal, with nothing trendy about it, and perhaps an extra thick mat with a deep, wide bevel.”

Something Whimsical: “With bright colors and a fancy-cut mat! We can cut shapes, names and letters into mats, or grooves and lines, and even draw on them ornately with a pen. You get to really use your creativity and imagination and think outside the box.”

THE ANATOMY OF A PERFECT FRAME

Masten breaks it down, piece by piece.

A wood frame: “Wood provides more protection for your artwork than metal or plastic.”

UV-filtering glass or plexiglass: “Necessary to block damaging ultraviolet light.”

A conservation mat: “Preferably a 100 percent cotton ‘rag mat,’ the best quality matting you can use.”

Archival mounting: “An acid-free or rag backing behind the artwork that’s either hidden or visible, depending on the style of framing, on rigid foam board.”